Block Storage in Windows Tech Overview, part 2

Welcome back to our two-part series on block storage technologies in Windows! If you missed it, you can read part one here, where we covered the basic concepts behind block storage in Windows. In part two, we will be exploring the specific Windows technologies that underpin block storage, their history, design, and key features and functionalities.

Windows implements some technologies to support volumes backed by several partitions, and also technologies to pool up disks into RAID-like configurations.

Logical Disk Manager (LDM)

Logical Disk Manager (LDM) allows users to create “dynamic volumes” that span multiple partitions and disks, support advanced features like mirroring, and resize without reformatting.

For this, the Windows Operating System distinguishes between a basic disk and a dynamic disk. On a basic disk, partitions are limited to a single contiguous area of the disk. On a dynamic disk, a volume can combine space from multiple disks or multiple areas on the same disk.

History

Introduced in Windows 2000, the LDM was designed to provide flexible and advanced disk management beyond the traditional “basic disk” system, on which volumes are mapped 1:1 to partitions.

Design

LDM builds a top of basic disk partitioning, by introducing small partitions of “logical disk metadata” to store LDM configuration. A disk on which LDM is set up is called a “dynamic disk.”

A logical disk metadata partition contains a database stored on each dynamic disk to track dynamic volumes, including:

- Volume type (simple, spanned, striped, mirrored)

- Disk membership and volume layout (which portions of which disks belong to the volume)

- Volume identifiers and metadata

A filesystem is mounted atop of a dynamic volume, which in turn can be spanned across several physical disks. To a filesystem, a dynamic volume appears as one contiguous block of disk space, as it were in the case of basic volumes. The LDM volume driver ensures the on-fly mapping between dynamic volume “virtual” space and “physical” space on dynamic disks.

Types of Dynamic Volumes

There are several types of dynamic volumes.

The difference between a “basic volume” and a “simple volume,” which both map to a single disk partition, is that a “simple volume” resides on LDM-configured “dynamic disks,” while a “basic volume” is a volume based on traditional “basic disk.” Additionally, a “simple volume” has a rarely-used feature to span across several non-contiguous partitions on a single dynamic disk.

Windows has a Windows Disk Management tool that allows users to convert disks to dynamic, and create dynamic volumes on top. Windows Disk Management hides “logical disk metadata” partitions from users, showing only partitions used by LDM to store volume data.

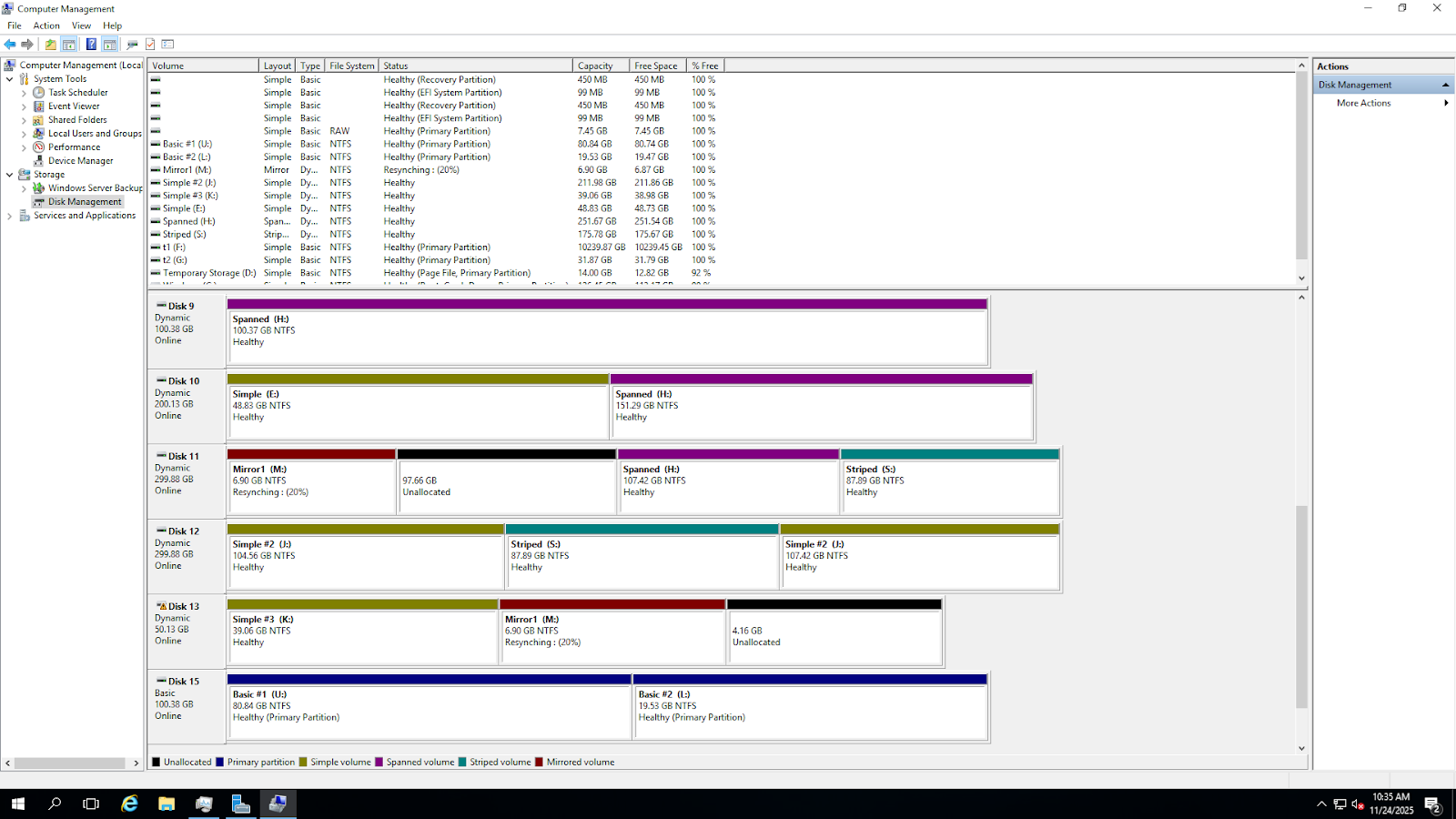

Figure 4. A sample dynamic disks configuration. Simple volumes are yellow, red are mirrors, teal are striped, purple is spanned, black are unallocated spaces, blue is basic volume.

Storage Spaces

Microsoft developed Storage Spaces to provide a flexible, software-defined new generation storage virtualization.

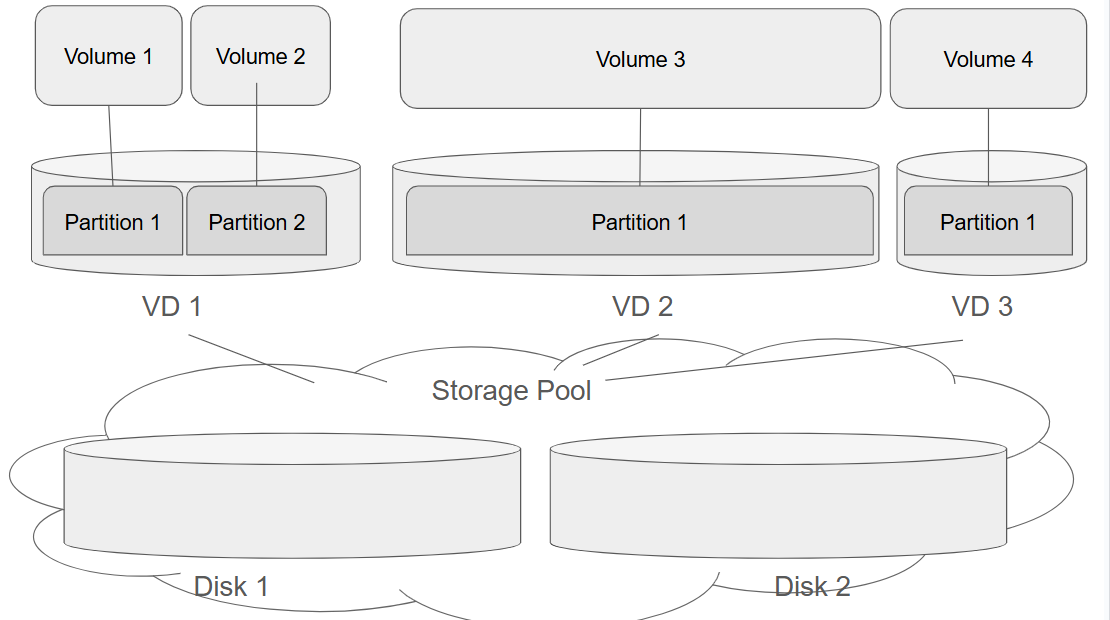

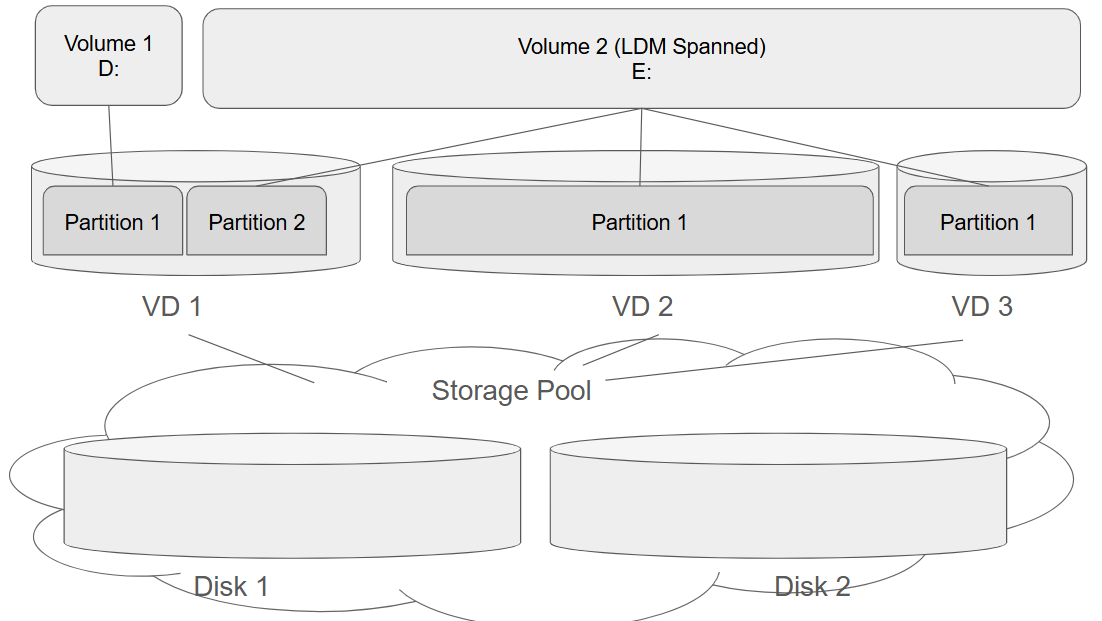

Instead of building volumes atop multiple partitions like LDM, Storage Spaces employs RAID-style technique to pool whole physical disks, not partitions, to form virtual disks. Virtual disks appear as regular disks to the user and can be partitioned, and volumes can be created atop of the partitions.

Figure 5. A sample Storage Spaces. 2 Physical Disks are in Storage Pool, and 3 Virtual Disks are created atop of Storage Pool. Virtual Disks can be partitioned like any other disks.

History

Key Milestones

- Windows Server 2012 / Windows 8 – Initial release; introduced features like storage pools, virtual disks, and resiliency options (simple, mirror, parity).

- Windows 8.1 / Windows Server 2012 R2 – Added tiered storage, allowing high-performance SSDs and high-capacity HDDs to be combined in a single pool.

- Windows 10 / Windows Server 2016+ – Improved reliability, performance, and management, including support for automatic tiering, and thin provisioning. Data migration allows to move data between physical disks, and remove physical disks from the pool on-the-fly.

- Storage Spaces Direct (S2D) – A modern evolution for hyper-converged infrastructures; allows pooling of local disks across multiple servers into a single resilient storage system. Used in clustered environments.

Design and Features

Storage Spaces allows users to pool several disks into a single Storage Pool. Whenever a disk is added to a pool, it is formatted by Windows to work as a Storage Spaces physical disk. Windows hides the physical disks added to the pool from users and applications.

Atop of storage pool, several virtual disks (also called “spaces”) can be created.

A virtual disk can be configured as simple, mirror, or parity. The configuration defines how storage space is mapped between a virtual disk and physical disks comprising the storage pool.

Thin provisioning

Storage spaces support thin provisioning. Thin provisioning is a storage management technique where the operating system allocates virtual disk space on-demand rather than reserving all physical storage upfront. In other words, the virtual disk can appear larger than the physical storage currently available.

For example, a virtual disk (Storage Space) is created with a specified size, e.g., 10 TB.

Initially, only the actual physical storage used by data is consumed from the storage pool.

As more data is written, Storage Spaces dynamically allocates additional physical space from the pool. If the storage pool runs out of physical space, writes will fail until more storage is added. A new physical disk can be added to the storage pool on-the-fly to increase the provisioned storage size.

Multicolumn

Multicolumn is a configuration option in Storage Spaces that controls how data is striped across multiple physical disks within a virtual disk. Essentially, it defines the number of stripes (columns) used for each write operation in a storage pool. The number of columns determines how many physical disks participate in storing each stripe: More columns → data spread across more disks → better parallelism and performance. Fewer columns → data spread across fewer disks → less parallelism but may use less physical disks for small pools.

Mirroring

Storage Spaces can maintain multiple copies of data on different physical disks within a storage pool to provide fault tolerance. This feature ensures that if one or more disks fail, your data remains safe and accessible.

When creating a mirror virtual disk, you can specify the number of copies:

- Two-way mirror: Two copies of every piece of data on two different disks

- Three-way mirror: Three copies of every piece of data on three different disks

Storage Spaces automatically writes the data to multiple disks simultaneously.

If a disk fails, Storage Spaces reads the remaining copy(s) to serve data to the OS without interruption.

Parity

Parity in Storage Spaces is a method of providing fault tolerance by storing redundant information (parity data) across multiple disks. Instead of duplicating all data like mirroring, parity uses mathematical calculations to reconstruct data in case of a disk failure. Parity requires an extra disk to keep parity information. Usually parity uses less disk space than full mirroring because only parity (not full copies) is stored.

Addition and removal

Physical disks can be dynamically added or removed from a pool. Storage Spaces updates the storage pool metadata to include the new disks. Also a disk can be retired and removed from a pool. Data that exists on the retiring disk is rebuilt onto other disks in the pool to maintain consistency and redundancy: data on the retiring disk are duplicated onto other disks, and (if required) parity is recalculated.

Tiering

Tiering is a feature in Storage Spaces that combines different types of storage media—typically high-speed SSDs and high-capacity HDDs—into a single storage pool. The system automatically moves frequently accessed (“hot”) data to faster storage and less-used (“cold”) data to slower storage.

Types of Virtual Disks

Implementation Details

Each physical disk in a pool has a small “metadata” area, which has all the data regarding the storage pool configuration, virtual disks, and mappings between physical disks and virtual disks. Each physical disk contains information regarding the whole pool, and metadata is mirrored across all the physical disks in a pool.

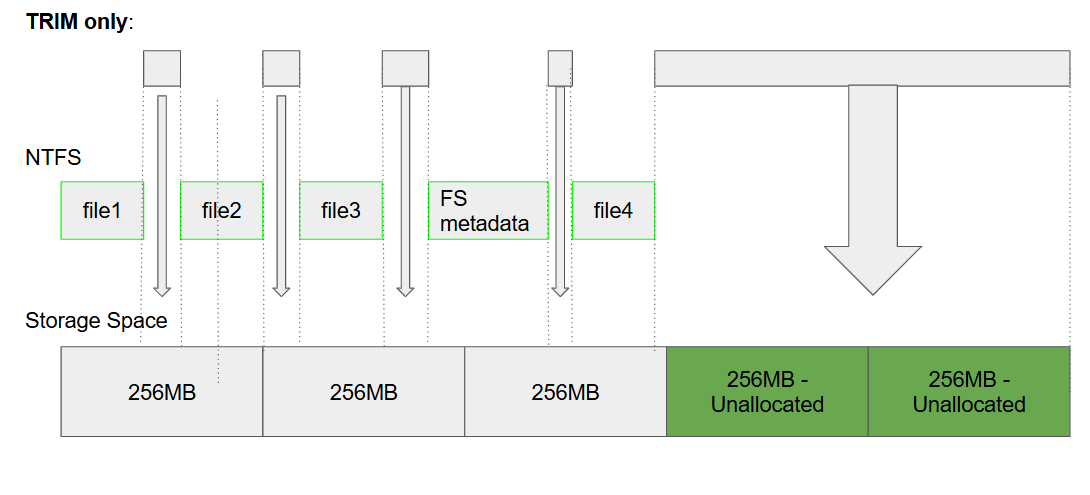

Disk space on physical disks added to the storage pool is divided into slabs. A slab is the fundamental allocation unit of capacity used inside a Storage Spaces pool. Instead of managing storage at the block or file level, Storage Spaces organizes physical disk space into large, fixed-size chunks—called slabs.

- Each slab is typically 256 MB in size.

- Slabs are assigned to physical disks within the storage pool.

- Virtual disks are constructed by mapping many slabs across multiple disks.

Slabs work in the following fashion:

- When data is written to a thin-provisioned virtual disk, Storage Spaces selects free slabs from the pool.

- For mirrored or parity spaces, corresponding redundant slabs are placed on different disks.

- Metadata keeps track of which slabs belong to which virtual disk.

The fact that data is stored in slabs has some side effects resulting in non-optimal use of disk space. Over time, writes, deletes, expansion, tiering, and disk removal can leave slabs:

- Unevenly distributed

- Partially used

- Stranded on specific disks

- Fragmented across the pool

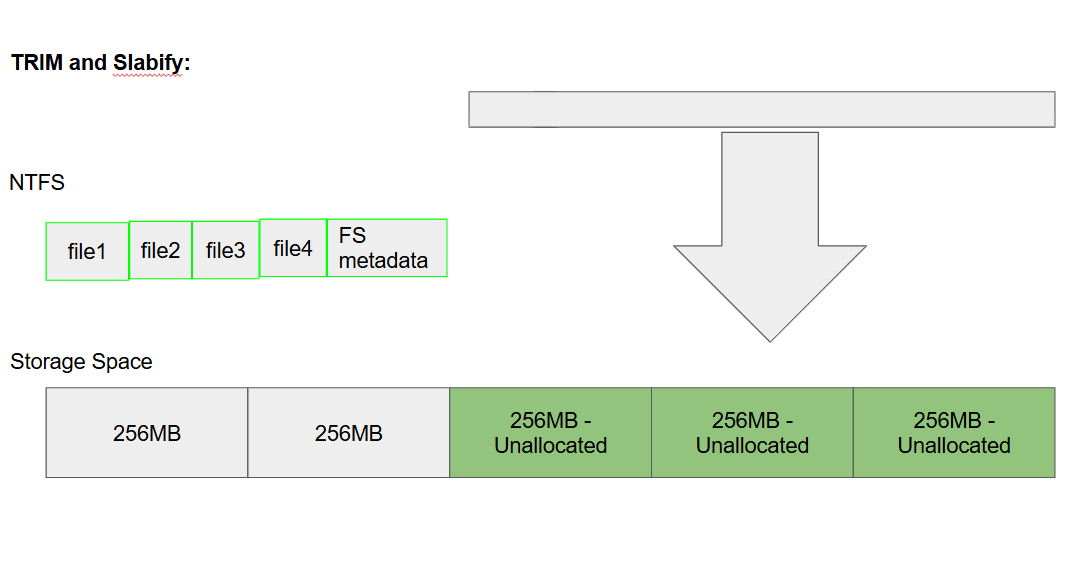

This reduces efficiency even if total free space seems sufficient. Defragmentation in Storage Spaces means reorganizing slab placement, also called “slabify”.

“Slabifying” refers to the process of reorganizing storage so:

- Data is stored in aligned, full slabs

- Free space becomes whole, unallocated slabs

- Storage pool metadata accurately reflects slab boundaries

The notification from the filesystem or defrag utility to free up a slab is called TRIM. On TRIM, Storage Spaces marks the related slabs as free inside the pool, and can be reused. It also passes TRIM down to SSDs if applicable, as SSDs make use of Trim for performance optimizations.

Figure 6. TRIM deallocates contiguous 256MB slabs in Storage Space. But it cannot deallocate smaller free space areas as they don’t fit into slab division.

Windows is configured to run Slabify optimization under a schedule, or can be launched manually via `Optimize-Volume` powershell cmdlet, or with `defrag.exe /K /L` command.

Figure 7. Slabify ensures the files are packed to the slab boundary, hence TRIM can deallocate more space.

A small addition: Hybrid Configurations

There are very few use cases when you may actually want to use a hybrid configuration, but just in case you are curious… can we combine LDM and Storage Space? Yes, it’s possible!

As Storage Spaces are disk-based, and LDM is volume-based, there is a possibility to combine them in the following way:

- Pool several physical disks

- Create several virtual disks

- These virtual disks will appear as normal disks in the system and legit disks to LDM

- Convert disks to dynamic. LDM will create its metadata and volumes atop of virtual disks.

Figure 8. An example of LDM Spanned volume E: built atop of partitions created on Storage Spaces.

Wrapping up

This concludes our two-part series on the basics behind block storage in Windows. If you’re interested in learning more about block storage and how to optimize it in the cloud, check out this on-demand webinar.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.webp)